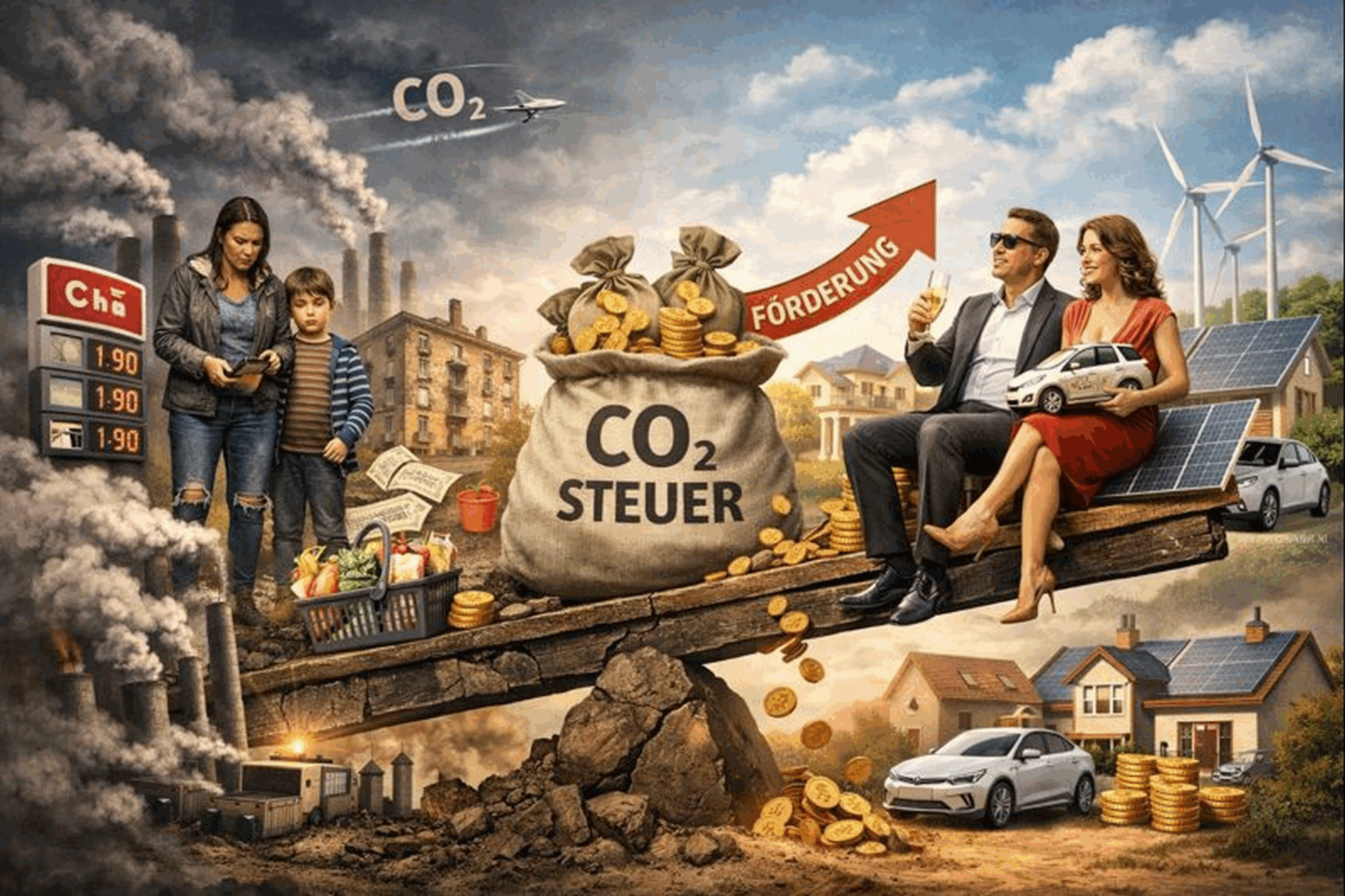

In 2025, the federal government collected €21.4 billion from CO2 certificates, but the burden is not distributed fairly. This is because CO2 costs are factored into almost all prices, as production, transport, and storage require energy. At the same time, higher-income households more frequently benefit from subsidies for electric cars, building renovations, solar panels, storage systems, and heating system replacements. Low-income earners, on the other hand, bear the full brunt of the price increases in their daily lives, as they can hardly benefit from these subsidies. The climate bonus promised when the CO2 tax was introduced was intended to compensate for this imbalance, but it has not been paid out to date and will remain politically unaddressed in the future.

Why CO2 costs end up in your shopping basket

The CO2 tax doesn’t just affect fuel and heating; it permeates the entire value chain. Shipping companies factor in higher fuel and energy costs, and manufacturers need electricity and process heat. Furthermore, refrigeration, warehouses, and retail operations increase the price of many products, so the tax is passed on to supermarkets and tradespeople as a silent surcharge.

Added to this is the price surge from ETS-1, the emissions trading scheme for industry and power plants. These companies buy certificates and pass the costs on through electricity and product prices. As a result, households indirectly contribute, even though they don’t see their own direct “CO2 expense.” Consequently, a broad price wave is created, which hits basic needs particularly hard.

Direct burden increases – and hits lower earners harder

Since 2020, the government has been increasing the price of fuels and heating oil through the national ETS-2. Last year, €55 was charged for every ton of greenhouse gas emitted from cars or heating systems. According to figures from the German Federal Environment Agency, consumers paid around €16 billion through this scheme, compared to €13 billion in 2024. This increases the pressure, and low-income earners feel it more quickly because energy costs consume a larger portion of their budget.

In addition, the government generated €5.4 billion by auctioning emission allowances in ETS-1. These costs are later passed on to end consumers through higher electricity prices and more expensive goods. A total of €21.4 billion flowed into the Climate and Transformation Fund (KTF), a funding pool designed to finance political priorities.

Climate money announced – then sidelined

CO2 pricing was intended to be socially cushioned, which is why climate money was proposed. Environmental economists wanted to redistribute the revenue per capita to provide net relief for low-income households. However, the plan remained a series of justifications and postponements: initially, policymakers cited a lack of account data, and later, the plan was abandoned altogether.

Instead of direct repayment, the KTF collects the billions and distributes them through various programs. Dirk Messner, President of the German Environment Agency, gave the instrument a positive assessment: “In combination with other effective measures, CO2 pricing provides crucial impetus for the climate-friendly transformation of our society.” At the same time, practical experience reveals a significant limitation, because without climate money, automatic compensation is lacking, particularly for low-income earners.

Subsidy logic rewards capital – and exacerbates inequality

A large portion of the carbon levy funds flows into renovation and modernization, primarily benefiting property owners. Programs also support electric cars, charging infrastructure, and investments in solar panels and battery storage. These measures require equity capital and therefore often reach households with larger financial reserves.

Those who rent or budget tightly often cannot initiate the crucial investments. Low-income earners still pay the CO2 costs through higher bills and rising everyday prices, while they cannot access the subsidies. This creates a redistribution through the mechanism of “paying through prices, benefiting through subsidies.”

Alternatives are lacking – the levy is insufficiently effective but burdensome

Affordable alternatives are lacking in many places for transportation and heating. Public transportation remains patchy in many regions, and electric cars remain expensive for many households. Replacing a heating system is also costly, and landlords often decide alone what happens in rental properties. Therefore, the steering effect remains limited, even though costs are rising. In particular, landlords pass on the costs of subsidized building renovations and the conversion of old heating systems to their tenants. This, in turn, disproportionately affects low-income earners.

At the same time, the government provides relief to industry through a CO2 price compensation for electricity costs, because these companies are subject to international competition. IG BCE union leader Michael Vassiliadis issued a clear warning: “The CO2 price is killing our businesses.” Nevertheless, the system does exhibit a difference, because corrective mechanisms apply to companies, while households do not receive any per capita compensation.

The bottom line: a price surge for everyone – a benefit for a few

The CO2 levy drives prices up across the board because energy is embedded in almost every product. Simultaneously, large portions of the subsidies end up with groups that can invest, thus shifting the relief upwards. Without climate-related payments, the automatic return to citizens, which was announced as a core social benefit, is missing.

The result is a system that places a heavier burden on those at the bottom and more frequently provides relief to those at the top. Low-income earners bear the brunt of the price increases in their daily lives, while subsidy programs often benefit those who already possess wealth. As long as the government does not introduce direct compensation, this social inequality will remain a consequence of CO2 policy. (KOB)